EMANUELE Tausinga didn’t show any warning signs. The outgoing and popular 22-year-old seemed to have it all: great friends, a talent for writing songs and mixing beats, and a bright future in the music industry.

But last October, he took his own life. Two weeks before his death, Emanuele confided in a cousin that he thought he might be depressed but conceded he didn’t know enough about depression to be sure.

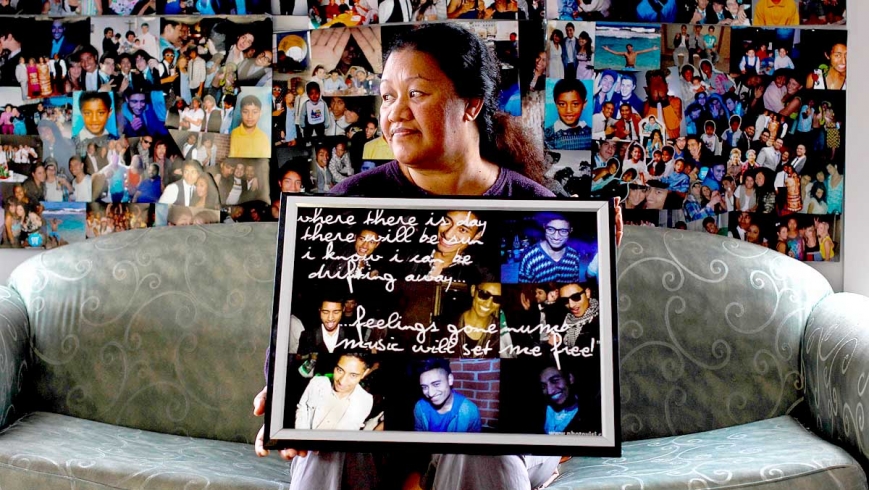

When his mother Kelela found out she tried to find someone to talk to him. She never imagined that just a couple weeks later her youngest child would commit suicide.

“Unless you are a professional you wouldn’t have seen [the signs] . . . there was no sign at all,” she said.

“He was a gentle being. He didn’t cut himself, he liked to dress good. His brothers used to tease him. Girls loved him.”

READ: Depression, suicide Wyndham’s growing scourge

In the weeks following Emanuele’s death, Kelela wanted to shut herself away from the world.

There were days where she thought she would drive herself insane, trying to work out why Emanuele had taken his own life.

But slowly, she came to realise that speaking to her family and counsellors was helping her make sense of her son’s death.

“Suicide is a sad, sad mental illness. People talk about cancer; why aren’t they talking about suicide?

“In my culture it is taboo, they think that your family is cursed if someone commits suicide. But speaking up helps you heal.’’

Kelela said she was grateful for the support she had received from her son’s friends, local businesses and the community. She said it had helped her through and taught her more about her son.

Now, she wants to do the same for other parents whose children have taken their own lives.

“I would like to look at starting up a group to assist parents and visit schools and get children to open up.”