– Click through the carousel above for our picture gallery of the Werribee River.

Once the most unprotected major river in Melbourne’s west, the tide has turned for Werribee’s grand waterway.

AS adventures go, it was pretty extreme for a monotreme (toothless mammal). This one, a young male platypus, recently took a wrong turn up a stormwater pipe and found itself high and dry near Werribee Plaza.

After being rescued and checked by vets it was returned to the Werribee River, but the episode again highlights the potentially perilous crossover in habitats – human and wild.

Werribee is known for the zoo and the old mansion, but the eponymous river is by far its greatest asset. The 110-kilometre waterway tells a story as old as the land itself. It trickles from the high country of the Wombat State Forest through spectacular glacial and volcanic gorges to the rich delta country of Melbourne’s food bowl to the estuary mouth.

The largest waterway on Port Phillip Bay’s western plain, it also serpentines through some of Australia’s fastest-growing local government areas.

As Melton, Moorabool and Wyndham continue soaking up population, safeguarding the river has become even more important to environmentalists who, after decades of campaigning, feel at last the tide is turning for the Werribee.

The release of the Werribee River’s formal water entitlement, plus an additional 850,000 million litres of unsold irrigation water purchased from the Department of Primary Industries, has provided the first decent flush of the river since the long drought years.

The river hasn’t looked so good in years.

“The Werribee River was very slow-stressed and suffering from the impacts of the drought,” Melbourne Water catchment manager Kate Nagato says.

“Now that we have made some environmental flow releases, we’ve created improved environmental conditions and improved the habitat for the aquatic plants and animals that live there.”

That includes the platypus population, and several recent sightings of juveniles, including the intrepid shopping centre visitor, are welcome proof of breeding after the long, long dry.

While the quantitative data shows increased oxygenation, improved pH and reduced pollutant levels, it’s the qualitative feedback that really underscores the waterway’s transformation.

“One of the dam operators at Melton Reservoir said: ‘You guys must be doing something right because I have worked up here for 20 years and I’ve never heard so many frogs; it’s deafening’.

“Obviously this work has outcomes for fish, frogs, waterbirds, platypuses and vegetation, but also for the community in social outcomes.

“We have improved recreational fishing and we’ve increased the number of waterbirds and wildlife for people to see when they go walking alongside their waterway.

“We have more attractive park areas – all those things aren’t just improvements to the environment, they are also improvements for the community.”

Werribee River Association (WRIVA)president John Forrester acknowledges Melbourne Water’s careful management of this major aquatic asset.

“The whole of the Werribee was not managed by anyone until 2004,” Forrester recalls.

“We were the only river in Victoria that had 80 per cent of its length under no manager.

“With no referrals authority, different organisations could do whatever they liked on the river, over the river, through the river.”

And so they did.

Forrester cites by way of example a housing development along Lollipop Creek at Wyndham Vale where developers dug out the existing dry creek to create a permanent water feature as a centrepiece of the estate.

“They dug this huge thing where it had only ever been a narrow little stream right in the middle of a stand of beautiful existing river red gums,” he laments.

“You go out there today and half of them are dead because river red gums like to be flooded once every blue moon and then go dry. They don’t like water permanently hanging around their roots, and that’s what killed them.

“But now everybody has to work with Melbourne Water and while things aren’t perfect, it has improved massively. We [environmental groups like WRIVA] may not win everything, but at least the river is a lot better managed and we have a real voice in that process.”

Rehabilitation of the Werribee is an ongoing job. In the 2013-14 financial year $1.4 million will be spent to improve native regeneration and revegetation to increase habitat along the river front.

As Melbourne Water’s river health officer for Lower Werribee, Alanna Wright explains it takes strong community partnerships to help bring the river back to scratch.

“It’s about education and providing amenities to community to get people appreciating their backyard and to regard that as their own asset,” Wright says.

“Out the back of Werribee township, the river really is a beautiful setting and it’s still in quite a natural state. That is really unique to have right in the city.”

Arguably, the Werribee has been under-appreciated and undervalued by too many for too long.

There are parts of the Werribee River that rival world heritage-listed parks for spectacular vistas, geological significance and flora and fauna values.

Listed as a reserve in 1907 and gazetted as a state park in 1975, the 575-hectare Werribee Gorge is a pocket rocket of wilderness areas, from the rock climber’s mecca of Falcons Lookout to the dramatic synclines and anticlines of the Daintree Cliffs.

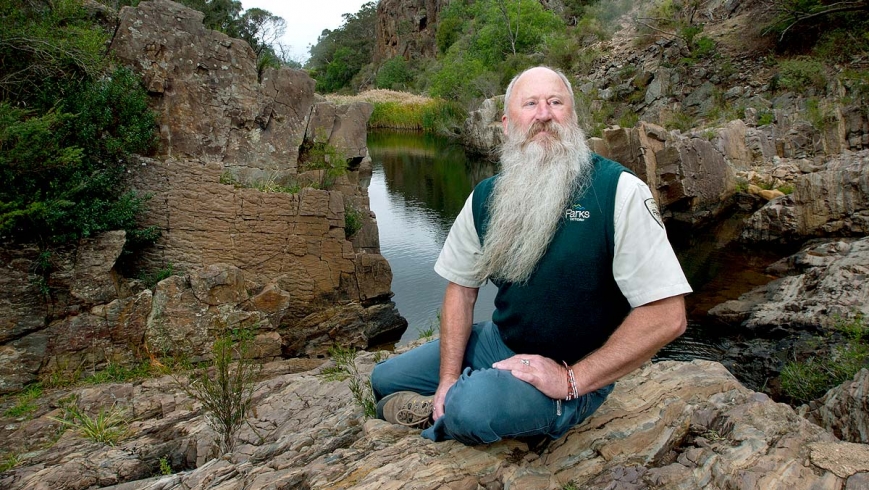

As Peter Box, Parks Victoria ranger-in-charge for the Moorabool management area, observes, it remains one of outer Melbourne’s great hidden gems.

“I think it’s the old story of the last place you visit is on your back doorstep,” Box says.

“People seem to travel miles to explore wilderness areas, but less than an hour from the city centre are places that can provide the same experience.

“Werribee Gorge may not be on the same scale as the Kimberley and more iconic parks, but it’s significant in its own right, mainly because of the geological values.

“You can be up in the gorge and feel like you are a million miles from modern living.”

1. Werribee River Association president John Forrester.

2. A platypus is released back into the Werribee River during the most recent survey.

3. Parks Victoria ranger Peter Box.