From the Williamstown commission flats to world title fights, boxing great Barry Michael’s first autobiography gives a blow by blow account of his life in and out of the ring, as Cade Lucas discovers.

“Cade, Williamstown back then, prior to the West Gate Bridge, was rough.”

I’d asked former world champion boxer Barry Michael what it was like growing up in Williamstown in the late 1960’s.

Many great fighters have used the ring as an escape route from poverty and hardship and by the sounds of things, it was no different for the man born Barry Swettenham in England in 1955, who’s family arrived in Australia as ten pound poms two years later and then moved into the Williamstown commission flats by the time he turned eight.

“There were junkies and drugs you know and my brother became a heroin addict. I lost about five mates over a period of 10 years from heroin overdoses,” he recalled.

“After the West Gate Bridge was built (in the 1970’s), things started to change. And now look at it, it’s about $1.6 million median house price.”

Now 69, Michael still lives in Williamstown, but like the suburb itself, his life bears little resemblance to the one he enjoyed in the days before the West Gate connected the inner west to the rest of Melbourne.

However, it’s not the bridge across the Yarra that’s responsible for Michael’s change in fortunes, but his long and storied career as one of one of Australia’s greatest boxers.

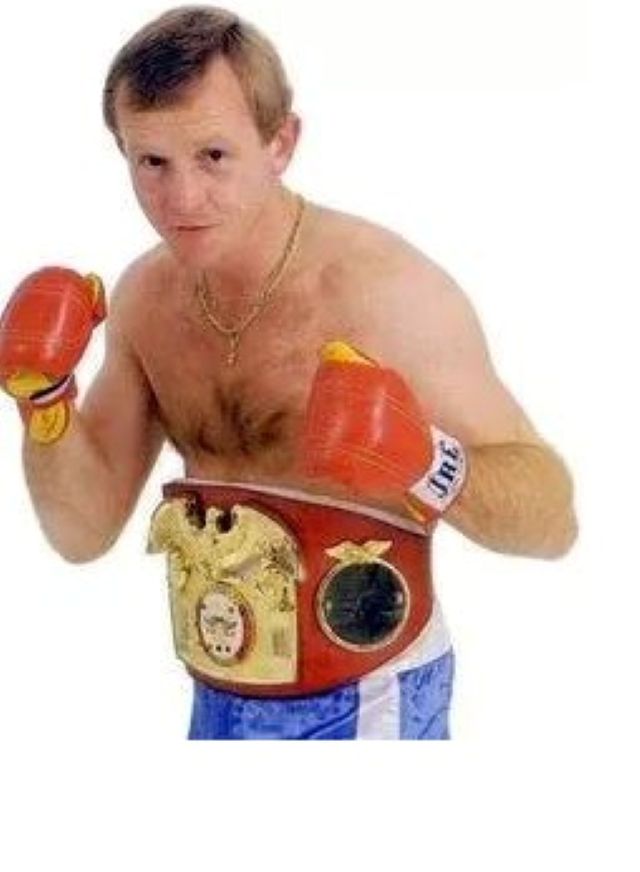

It’s a career that took Michael from sparring sessions in an old church hall on Melbourne Road to rings across Asia, the United States and United Kingdom, and most famously, to Festival Hall in 1985 where he finally won a world title, resting the super featherweight belt off for former friend, but then bitter foe, Lester Ellis, in one of the biggest domestic bouts in Australian fight history.

That and many other fights, both inside and outside the ring, plus his post-retirement career as a fight promoter and commentator are detailed in his first autobiography, Last Man Standing, which will be released in July.

The title is a reference to Michael’s endurance in the ring, where he was never knocked out and regularly took opponents the distance.

It could equally apply to his life post-retirement, which has been longer and more successful than many of his pugilist contemporaries, particularly others from disadvantaged backgrounds who often find the fame and fortune won inside the ring evaporates once they hang up the gloves.

For Michael, while his upbringing in the Williamstown commission flats in the 1960’s might’ve been rough, boxing wasn’t his only route out of it.

“I was always good at school. I did my matriculation and I wanted to do economics would you believe,” he recalled incredulously.

Michael was ultimately offered the chance to study psychology, but by this stage, the 16-year-old was already a keen student of the sweet science thanks to the exploits of the legendary Lionel Rose.

“I was in love with Lionel Rose and Johnny Famechon, they were my idols, especially Lionel.”

He was far from alone.

Rose winning the world bantamweight title over Japan’s Fighting Harada in Tokyo in 1968 made him an instant national hero.

More 100, 000 people lined the streets of Melbourne when the first Indigenous man to win a world boxing title returned home.

The late 1960’s were the halcyon days for Australian boxing, with Rose and world featherweight champion Famechon household names and TV Ringside beaming fights into living rooms every week.

Having deferred his studies and turned professional, Michael soon became Rose’s sparring partner and friend and dreamt of emulating his idol’s world title success.

But as the 60’s became the 70’s and Rose and Famechon retired, the Australian public’s interest in the fight game went with them.

Minus the public adulation of his predecessors or the pay-per-view millions earned by those who followed, Michael spent his peak years fighting overseas, largely in anonymity.

“It was very difficult to get fights for years,” he said.

“So I’d get on a plane and go anywhere for $1000 bucks to fight 10 rounds. Thus I fought in Indonesia five times, the Philippines, South America, Wales, England, the United States, all over the world.”

All over the world, but no world title.

As ever with boxing, politics and promoters got in the way and by the early 1980’s, Michael’s chances of reaching the pinnacle were rapidly passing him by.

Fortunately, the Australian fight game was finally showing signs of life, driven by Jeff ‘the Marrickville Mauler’ Fenech and a young fighter from Melbourne who Michael knew well: Lester Ellis.

Like Michael, Ellis was born in England, but grew up in Melbourne’s western suburbs in West Sunshine.

Like Michael, Ellis began boxing in his early teens and showed serious promise in similar weight divisions..

Their similarities brought them together as training partners and friends, but by the mid-80’s their differences had pushed them apart.

Ellis was almost a decade younger and unlike Michael, had a distinguished amateur career, a springboard from which he quickly rose through the ranks upon turning professional in 1983.

Just two years later, Ellis defeated South Korean Hwan-Kil Yuh to do what the older man had spent more then a decade trying and failing to do: win a world title.

Not only did Ellis have what Michael wanted, he also had Michael’s former trainer, Dana Goodson.

The American had walked out on Michael after he suffered a serious foot injury during a training camp in Miami.

Upon returning to Melbourne, Michael was shocked to learn Goodson was now in Ellis’ corner.

Relations hit rock bottom, yet after winning his world title, the Ellis camp unwisely booked Michael for his second and last title defence.

In a match up as bitter as it was anticipated, Ellis and Michael met for the IBF Super Featherweight world title at Festival Hall on July 12 1985.

In the same venue that once hosted his favourite program, TV Ringside, Michael produced the fight of his life to win by unanimous decision over 15 rounds.

He was a world champion at 30.

Michael made three successful defences before losing the title to American Rocky Lockridge in 1987, the final fight of his career.

But was another fight outside the ring that brought about the end.

Four months before the Lockridge fight, Michael was severely bashed in a Melbourne nightclub by notorious organised crime figure Alphonse Gangitano and his associates.

“He just jumped me Gangitano, I never got a single punch or anything,” said Michael who speculates bad blood from a nightclub fight a decade earlier and the lack of a re-match with Ellis something the gangster was rumoured to have interests in, as reasons for the ambush.

“They just pinned me on this couch and smashed the shit out of me. My nose was smashed with a glass ashtray they reckon. Chopper Read said I’d never be able to walk and talk again, they smashed me so bad.”

Michael not only walked and talked, but fought again.

However the injuries to his nose from the bashing meant he was never the same.

“My nose was under my left eye (after the bashing) and I had to have it re broken and reconstructed, and it wasn’t the same in the gym,” he said.

“It broke in the first minute against Lockridge in my last fight.”

Gangitano was murdered in 1998 as part of Melbourne’s underworld war, while Michael entered into a long career as a boxing promoter and commentator, while also pursuing interests in real estate.

After long-wanting to write a book, Michael was five chapters in when his third wife Sue, died suddenly in 2023.

With help from his publisher and using some of the determination that saw him win 48 times from 60 fights, Michael pushed through and will launch the book on July 12.

The date marks the 40-year anniversary of his fight with Ellis, his former foe and now friend who has written the forward.